Source : CTC Sentinel, Westpoint

The Paris Attacks and the Evolving Islamic State Threat to France

By Jean-Charles Brisard

The Paris attacks of November 13, the deadliest terrorist attacks on European soil since the Madrid bombings on March 11, 2004, were the latest indication that the Islamic State has morphed from a regional to a global threat, a threat that could increase if the Islamic State decides to further “weaponize” its Western recruits. After the January 2015 attacks in France, several foiled plots provided evidence of planning and operational connections with Islamic State cadres or militants abroad. The complexity of the latest attacks and the level of planning and preparation required suggest Islamic State fighters are adapting to the law enforcement and security measures arrayed against them, which raises significant concerns and questions about the viability of the status quo in the European security paradigm.

The Paris attacks of November 13 provide all the patterns of a complex plot involving a high level of planning and preparation, which contrasts with all other plots and attacks in the West that have been linked to the Syrian and Iraqi context since 2013.

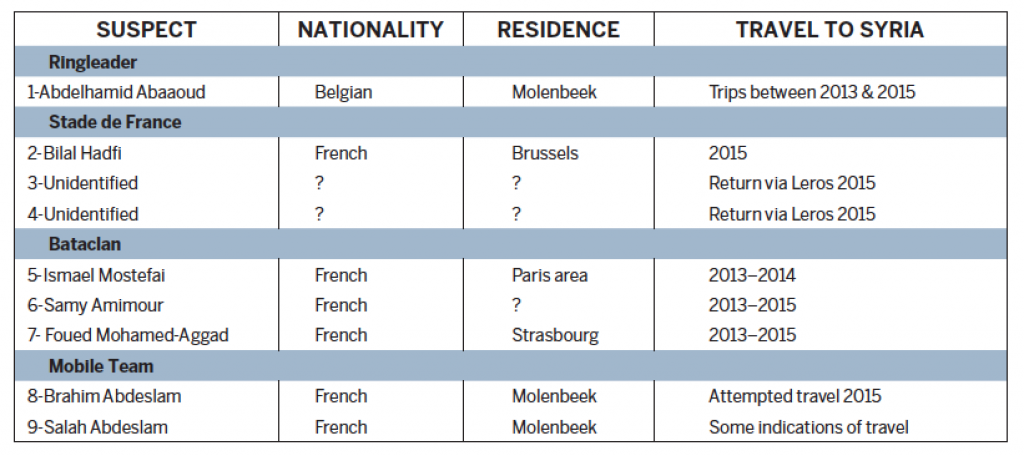

So far, the investigation has found that at least eight of the plotters, including attackers and facilitators, were foreign fighters returning from Syria. Aside from the ringleader, all of those identified as carrying out the attacks were French nationals. Several were based in the Molenbeek area of Brussels, Belgium. The ringleader was a well-known Belgian foreign fighter, Abdelhamid Abaaoud. He and a childhood friend, French foreign fighter Salah Abdeslam, are believed to have planned, prepared, and coordinated the attacks. Both men had been convicted in February 2011 for their joint involvement in armed robberies in Belgium.

Most of the plotters re-entered Europe in August, three months before the attacks, and at least two of them entered Europe in October via the refugee flow through the Greek island of Leros. Once in Europe, at least one of them, Salah Abdeslam, made frequent roundtrips from Brussels to Paris in September and October. In September, he bought detonators outside Paris. In November, he and his brother Brahim rented three cars in Brussels and used online services to book several apartments, hotel rooms, and a house in and around Paris to accommodate the plotters. The weapons used by the perpetrators were bought online or obtained through criminal networks.

The plan involved three coordinated teams acting simultaneously in various places in Paris: the iconic Stade de France, where three suicide bombers blew up themselves after failing to enter the stadium; the Bataclan concert hall, where three attackers were killed or blew themselves up after shooting and taking hostages; and central Paris, where a mobile team fired on several restaurants and cafes. The French prosecutor later indicated that Abaaoud and an accomplice, who were killed during the siege of an apartment in Saint-Denis near Paris on November 18, had planned another attack targeting a commercial center and a police station in the Paris business district of La Défense set to take place the same day or the day after. A witness also stated Abaaoud had spoken of other plans to attack Jewish targets, transportation systems, and schools.

Salah Abdeslam managed to escape France after he apparently abandoned his suicide vest and was picked up by two accomplices, while Abaaoud remained in France to supervise the outcome of the plot and plan new attacks. The French prosecutor provided striking details on Abaaoud’s whereabouts during the attacks in central Paris. He stated that he was caught on videos on the Paris Metro heading to the areas of the shootings where he spent two hours, including near the Bataclan concert hall during the attack, according to data collected about his mobile phone location.

In a new development, the author can reveal that Abaaoud’s presence near the Bataclan was confirmed by at least one witness formally interviewed by investigators. The witness, who was parked in a car on a dark street about three short blocks away from the Bataclan shooting, testified that Abaaoud was huddling in the doorway of a residential building where he remained for about one hour.

The witness described him as very agitated and shouting into the phone with an earpiece. The witness left and came back to the car several times and each time Abaaoud was still there yelling into his phone. After the assault, the witness returned a final time and came across Abaaoud in full light at the end of the street and was struck by his unusual face with a long nose. The witness later remarked that Abaaoud’s head was shaved and that he was wearing layers of unusually large, loose clothing. Having seen his face, the witness immediately recognized Abaaoud days later when pictures of the terrorist emerged in the press. The presence of Abaaoud in the immediate vicinity of the attacks provides an indication of his degree of implication in the supervision and control of the plot and suggests he was giving direct orders and instructions to his team inside the Bataclan during the shootout.

Abaaoud’s control in real time over the various phases of the plot was further evidenced by the phone data indicating he was communicating with Bilal Hadfi, one of the three Stade de France suicide bombers, in the minutes leading up to and in the very moment when the first of the three blew himself up.

The fact that the November 13 attacks were claimed in the name of the Islamic State in a statement read by Fabien Clain, a veteran French foreign fighter, was likely not coincidental. Fabien Clain was a close friend of the Mohammed Merah family in Toulouse before his family settled in Brussels. Clain was also convicted in 2005 for his participation in a network recruiting fighters for Iraq. He finally joined the Islamic State in Syria in 2014 where he is believed to have reached an important rank. More significantly, his name had been associated with a 2009 plot against the Bataclan, the very same target that was hit on November 13. Because of his background, his role in the genesis and planning of the Paris attacks could have been more than just symbolic.

In probing links between the Paris attacks and overseas terrorists, other persons of interest to French investigators are Salim Benghalem and Boubaker el-Hakim, who are both believed to be senior operatives of the Islamic State, based in Syria.

The Islamic State Campaign to Attack France

The Paris attacks, which were the deadliest terrorist attacks on European soil since the Madrid bombings on March 11, 2004, did not come as a surprise. If this specific attack was not anticipated, one like it was expected.

For the last 30 years, the involvement of French jihadists in conflicts in Afghanistan, Chechnya, Somalia, and Iraq always had implications for French national security in terms of propaganda, recruitment, support, or terrorist acts. A 2013 study found that among Western foreign fighters, one in nine returned to perpetrate attacks, or a rate of 11 percent. In France, according to the former leading counterterrorism judge Marc Trevidic, 50 percent of the French jihadis who fought abroad reengaged at some point in terror networks after they returned, and all major terror plots foiled in France since 2000 involved returnees. Such plots included the Strasbourg Cathedral Plot in 2000, the U.S. embassy bombing plot in 2001, a chemical attack plot in 2002, and plans to bomb the Eiffel Tower and the Notre-Dame Cathedral in 2010.

France currently has the largest contingent of foreign fighters from Europe in Syria and Iraq. More than 2,000 French citizens and residents are involved in Syrian and Iraqi jihadi networks. Among them, 600 are believed to be fighting alongside terrorist organizations abroad and 250 are believed to have returned. France alone accounts for one-third of all Europeans involved (6,500). Sixty percent of European jihadists originate from three countries: France, the UK, and Germany. It is estimated that 1,500 of them, or 25 percent of the total European citizens and residents involved, have returned to their home country.

Despite analysis depicting the Islamic State threat to the West as exaggerated,10 all the warning signs were there that the group would escalate from having primarily a regional focus to becoming a more global threat. These signs were in the group’s ideology, the repeated statements by its leaders that it seeks confrontation with the West, and its threats in response to the international coalition air campaign against it. And it was clear that even if the group itself did not embrace a strategy of attacking the West, the thousands of foreign fighters it had recruited could take matters into their own hands.

France has long been a target of modern jihadi organizations, and the Islamic State’s determination to target the country, whether by inspiration or direction, was evidenced in many plots conceived since 2013 and even more significantly since January 2015.

This year, France has experienced both simplistic Islamic State-inspired plots and more complex attempts from foreign fighters involving tactics such as multiple attacks, explosives, and suicide attacks intended to cause mass casualties.

Investigations into the January 2015 attacks on the Charlie Hebdo satirical magazine and a kosher store in Paris revealed planning and operational connections with Islamic State cadres or militants abroad who assisted in instructing, advising, or directing the plotters. Amedy Coulibaly, the kosher store attacker, received instructions by email from someone overseas who seemed to have knowledge of both coordinated plots, including the Charlie Hebdo attack by the Kouachi brothers.

Since then, similar directional links have been uncovered in most, if not all the foiled plots, including a project to target churches in Villejuif in April,c a plot against a military base near Perpignand on the southern coast in July, a plan targeting a concert hall in August, the foiled Thalys train attack in August, and a planned attack against a naval base in Toulon in October.

Table 1: Paris Attack Suspects by Nationality, Residence, and Travel to Syria.

The data in the table is based on French and international media reports and information received by the author from investigators. A tenth unidentified attacker blew himself up during the French commando raid in Saint-Denis on November 18. Several of the plotters were resident at some point in the Molenbeek district of Brussels.

Since the beginning of the year, security services had knowledge of mounting threats from European fighters, including the suspected ringleader of the November attacks, Abdelhamid Abaaoud, whose name had already been associated with several plots against France in 2015, including the church and train plots.12 Plotters described him as someone obsessed, who wanted, at all cost, to recruit volunteers to carry out attacks in Belgium and France.

The most striking signal was provided in August when a returning French foreign fighter arrested on August 11 told investigators he attended a training camp for a week in al-Raqqa before being “instructed” by Abaaoud to launch an attack in France on a soft target to achieve maximum casualties. The chosen target was a concert hall. Abaaoud had provided him a USB stick containing encryption software and €2,000.

Abaaoud had been plotting against European targets since the very beginning of the year. An earlier attempt similar to the Paris attack was foiled on January 15, 2015 in Verviers, eastern Belgium, when authorities raided a safe house. The ensuing firefight ended in the deaths of two individuals and a third suspect was arrested. The raid disrupted a plot involving ten operatives, most of them Islamic State foreign fighters, possibly targeting police or the public. The suspected leader of the group, Abaaoud, directed the operation from a safe house in Athens, Greece using a cell phone, while other group members operated in several European countries.

Interestingly, at the time Abaaoud was already using deceptive tactics to avoid border controls. He even faked his death to deter efforts by law enforcement officials to track his activities. For that purpose, Abaaoud’s family received a call in late 2014 that he had been killed while fighting in Syria. Several members of the group were also able to freely travel across borders. Abaaoud would boast that he was able to return to Syria after the Verviers raid despite international arrest warrants, according to an interview featured in the February issue of the Islamic State’s Dabiq magazine.

The Future Threat

The Paris attacks and the plots uncovered since January provide several important indications of the status and evolution of the threat against France and Europe. The Islamic State’s move toward “weaponizing” its Western recruits, if sustained, may likely lead to a major increase in the level and scale of the terrorist threat.

The Islamic State and its operatives have demonstrated their intention and ability to plan complex plots involving a large group of terrorists. This marks a change from previous trends in Europe, where individual terrorist attacks accounted for 12 percent of all attacks between 2001 and 2007, while rising to between 40 and 45 percent of all terrorist attacks since 2010. The indiscriminate nature of the targeting in the Paris attacks was also a departure from previous trends. Attacks on random targets had decreased since 2008, representing 28 percent of all terrorist attacks in the period since then while discriminate attacks constituted 55 percent of all attacks since then. Despite the emergence of larger-scale plots, the threat represented by individuals or microcells will remain due to the continuous appeals and threats from the Islamic State leaders and militants. But the Islamic State’s apparent desire to maximize casualties and the impact of plots against the West may result in it orchestrating more sophisticated plots, involving a high level of planning, preparation, and commitment, and trained fighters instead of inspired sympathizers. One study based on jihadi attacks and serious alleged attack plots in the West from January 2011 through June 2015 found that foreign fighter attacks were far more deadly on average (7.3 deaths per attack) than attacks without foreign fighters (1.2 deaths per attack).

Given the scale of the Paris attacks, it is likely that Islamic State-linked plots will increasingly draw on foreign fighters with a criminal background and networks in their native country, especially operatives such as Abdelhamid Abaaoud and Salah Abdeslam, who have the ability to leverage violent extremists in their home countries to boost support and facilitation, as well as the skill-sets to obtain weapons and evade security services.

The fact that, as the Verviers and Paris plots illustrated, Islamic State-linked plots have elements of planning in multiple countries is another pattern creating significant obstacles in their detection and disruption.

The difficulties of preventing Islamic State-linked terrorism has been compounded by the use of varied tactics in such plots initiated against France and Europe this year, including multiple coordinated and synchronized attacks, suicide bombings, hostage taking, and Mumbai- and Kenya-style shootings.

The decision by the Islamic State to launch “dynamic” multi-hour terrorist operations in Paris instead of a “static” attack of compressed duration was probably intended to delay the ending of the event, which would increase its impact, and potentially allowing additional planning and waves of attacks. In that regard, as mentioned above, Abaaoud and an accomplice had targeted a commercial center and a police station in the Paris business district of La Défense, and also considered targeting the Jewish community, transportation, and schools.

The fact that three of the latest Islamic State-linked plots and attacks in Europe (the concert hall plot and Thalys foiled attack in August, and the November 13 Paris attacks) were intended to inflict indiscriminate mass casualties may signal a shift from previous selective and symbolic targeting by Islamic State-inspired or directed militants targeting high-value targets such as religious communities, police, and military personnel. This shift might be a strategic move by the Islamic State leadership, but it is more likely temporary and linked to specific planners, including the Abaaoud network. It may also suggest progressive adaptation to law enforcement and security measures by attempting to make the threat less predictable.

The Paris attacks of November 13 have also demonstrated major failures in European border control policy and the exchange of information between European Union-member states. The fact that most of the perpetrators and facilitators of the attacks were able to travel and slip undetected into the heart of Europe, and then travel back and forth between Belgium and France to prepare the attacks raises significant concerns about European law enforcement agencies’ ability to detect and investigate transnational threats, and raises questions about the viability of the status quo in the European security paradigm.

Cet article est aussi disponible en Anglais